My latest piece — in which I venture into more political writing for TAC — argues that the failures of Euclidean zoning antagonize some of the most fundamental priorities of American traditions on both the Left and the Right; and that there may be an opening for some agreement between people with a broad range of philosophies. For example:

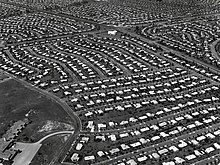

During the postwar era—when suburbs and cars were the way of the future, and cheap, undeveloped land surrounded all our cities—the postwar type of zoning seemed a reasonable trade-off for many conservatives. While it regulated the private land market, it was locally enacted. In addition, its intent was to protect a broad base of individual, private owners.

Today, things have changed. Many of our most prosperous regions have been effectively built-out—few undeveloped lots remain—and laws preserve building patterns from the less populous 1950s and 1960s. This in turn has created an artificial shortage of housing units to which local markets cannot respond. Property owners who could benefit from making more intense use of their parcels find their hands tied by local zoning. Families and individuals are priced out of regions where opportunities are strongest. Personal potential and mobility are limited. And local governments become powerful fiefdoms, selectively approving lucrative projects for (often) politically-connected developers while preventing smaller owners from similarly maximizing returns.

Meanwhile, from the Left:

If local zoning had simply permitted [working-class neighborhoods in major cities] to absorb growth as it occurred, it is likely many longtime residents would never have been priced out by rising rents or property taxes. This means that more young people could have remained in their home communities and benefited from deep ties to family, social networks, and local wealth; and space could also have been made for new immigrants (and internally-migrating Americans) on much friendlier terms. Instead, our inability to accommodate change at the neighborhood level has resulted in the attenuation of countless social ties; the loss of myriad old communities; and an increased degree of hostility and resentment between competing, but similarly powerless groups, over space that never needed to be so scarce. If anything should outrage even the most nominal leftist, it is a bureaucratic policy that pointlessly pits the American working class against new immigrants over something as fundamental as the need for decent housing.

Feel free to join in the discussion at the bottom.