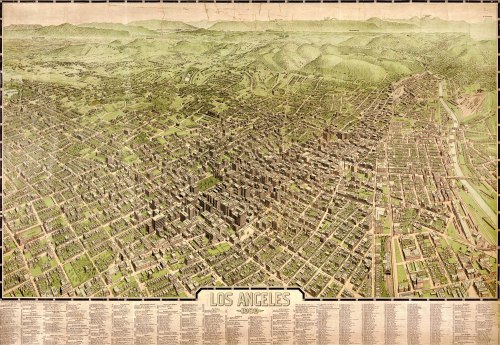

Here’s a three-dimensional, color map of Los Angeles, in 1909. It’s interesting. You can see the urban core that was beginning to take shape: the concentration of zero-lot line buildings, the canyons of concrete, the traditional green squares, the grid of warehouse blocks near the railroad tracks. Had it not been for the interruption by history — motor vehicles, modern zoning — a more traditional big city might have evolved there.

Here are a couple of surviving examples that I found of urban fabric in the core of Los Angeles, from which you could kind of envision an alternate pattern of how Southern California might have developed:

Broadway / 7th Street, Los Angeles.

Spring / West 4th Streets.

Just north of the urban core is Bunker Hill. You can see it in the bird’s-eye view, above, where the land rises behind the dense grid of streets, and the structures transition from commercial to residential. Most of what was once there is gone today. Here’s an old photograph, looking across Pershing Square:

Raymond Chandler described the late stages of the neighborhood’s decline in his 1942 novel, The High Window, as only he could do:

Bunker Hill is old town, lost town, shabby town, crook town. Once, very long ago, it was the choice residential district of the city, and there are still standing a few of the jigsaw Gothic mansions with wide porches and walls covered with round-end shingles and full corner bay windows with spindle turrets. They are all rooming houses now, their parquetry floors are scratched and worn through the once glossy finish and the wide sweeping staircases are dark with time and with cheap varnish laid on over generations of dirt. In the tall rooms haggard landladies bicker with shifty tenants. On the wide cool front porches, reaching their cracked shoes into the sun, and staring at nothing, sit the old men with faces like lost battles.

In and around the old houses there are flyblown restaurants and Italian fruit stands and cheap apartment houses and little candy stores where you can buy even nastier things than their candy. And there are ratty hotels where nobody except people named Smith and Jones sign the register and where the night clerk is half watchdog and half pander.

Out of the apartment houses come women who should be young but have faces like stale beer; men with pulled-down hats and quick eyes that look the street over behind the cupped hand that shields the match flame; worn intellectuals with cigarette coughs and no money in the bank; fly cops with granite faces and unwavering eyes; cokies and coke peddlers; people who look like nothing in particular and know it, and once in a while even men that actually go to work. But they come out early, when the wide cracked sidewalks are empty and still have dew on them.

The urban fabric of Bunker Hill was almost completely demolished in the 1960s under a massive redevelopment plan. For a sense of what was lost: George Mann, a Los Angeles photographer, took this picture in 1959:

Grand Avenue / 2nd Street. Photo by George Mann, courtesy of Dianne Woods and the George Mann Archives. (Fair use.)

A few years ago, I wrote

A few years ago, I wrote