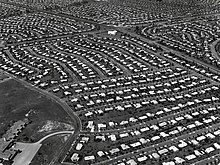

The Wall Street Journal reports today that the United States needs 5.5 million new housing units. That’s a serious backlog. As a nation, we are not building homes quickly enough to keep up with population growth. This is the story behind the soaring prices we hear about in the news. Digging a bit deeper, it could also be a key factor in falling birthrates and adults who continue to live in their parents’ home. So, how do we get serious about building the homes people need? Shouldn’t the market be driving toward an equilibrium?

The market is hot (again), but the shortage is chronic. Part of the problem is undoubtedly zoning, especially in the regions with the greatest demand. In New Jersey, the Mount Laurel doctrine has been a valuable tool since the 1970s, when it established the basic legal principle that zoning is a state action that may not be used to exclude entire classes of state residents from particular communities; to do so is inconsistent with the 1947 New Jersey Constitution. (I simplify, but not too much.) The New Jersey Fair Housing Act, which the state legislature enacted in 1985 to follow the Mount Laurel cases, has helped produce a significant number of regulated affordable units, over the years. Yet Mount Laurel, though based on an exemplary principle, has invited constant political resistance. Its implementation has been obnoxiously complicated. Worse, it does little tangible good for New Jersey residents who don’t fall into the income band for affordable housing — or even many who do, because the demand always outstrips the availability of units.

Yet today, more than four decades after Mount Laurel crystallized the concept of exclusionary zoning, the impacts of a chronic housing shortage reach much further up New Jersey’s socioeconomic hierarchy than they did in 1974, when the first case was argued before the New Jersey Supreme Court. That is, there remains a severe shortage of decent, affordable housing units for poor and working-class people. But there is also a dearth of homes for sale (or rent) at higher price points, in many communities — a bottleneck similar to ones that have formed, to greater or lesser degrees, in other high-cost metropolitan regions throughout the world. Not surprisingly, out-migration continues apace. Yet immigration keeps the overall population going up. Those who stay pay more for less.

So how can this unmet housing need be met? And should housing policy necessarily be bureaucratized, or could it be pursued more effectively by unlocking the private production of more market-built, non-income-regulated units? One concept that the Mount Laurel formulas acknowledge is filtering. That is, older units (often well built!) will become more affordable, through market forces, when newer units are produced quickly enough to soak up a lot of the high-end demand. This is how, for example, poor and working-class people inherited the incredible (if neglected) Art Deco apartments of the Grand Concourse (for a time — they are getting expensive again!).

I believe the next frontier will be a process of artfully (at best) customizing and improving zoning laws. Done wisely, this will foster the construction of market-rate homes that complement our existing neighborhoods while improving land values and strengthening public finances.